While the Soviets liked dogs and the Americans preferred rats or monkeys, the French were the only ones who attempted to send cats into space.

+ Video captures a trio of cats working out to get in shape for the summer

+ 10 Things Humans Do That Cats Dislike

+ Zoo releases cute video featuring the ‘deadliest cats in the world’

Even though they were far behind the Soviets and Americans in the space race, France was determined to also be a spacefaring nation.

They began building a new generation of rockets shortly after World War II, and by the early 1950s, they were testing a model called Véronique: a sounding rocket that would briefly soar into space before free-falling back to Earth without reaching orbit.

The early launches departed from a base in the high desert of the Sahara, in the French colony of Algeria at the time. On February 22, 1961, France became the third country to launch an animal into space: a rat named Hector, who flew aboard a Véronique rocket on a brief suborbital flight.

But the French had bigger ambitions. They were looking for another small mammal to send into space, one larger than a rat but small and light enough to travel in the narrow nose cone at the tip of a Véronique rocket.

While rabbits or small dogs could have been suitable, there was a significant reason for choosing cats: at the time, they were widely used in France for neurophysiological experiments, examining how the brain and nervous system functioned.

It required a containment for the animal, instruments to measure and transmit data about its physical condition, a cartridge to absorb the carbon dioxide it exhaled, transponders, beacons, and parachutes.

In the mid-1963, the French Aero-Medical Research Centre, Cerma, selected 14 cats for flight school: all females, acquired from a dealer and recommended for their calm temperament.

They were trained for about two months, practicing sitting in a container for hours, being spun in a centrifuge, and enduring the loud noise of the rocket’s engine. In early October, the cats that seemed to tolerate it best were taken to Algeria to prepare for the launch.

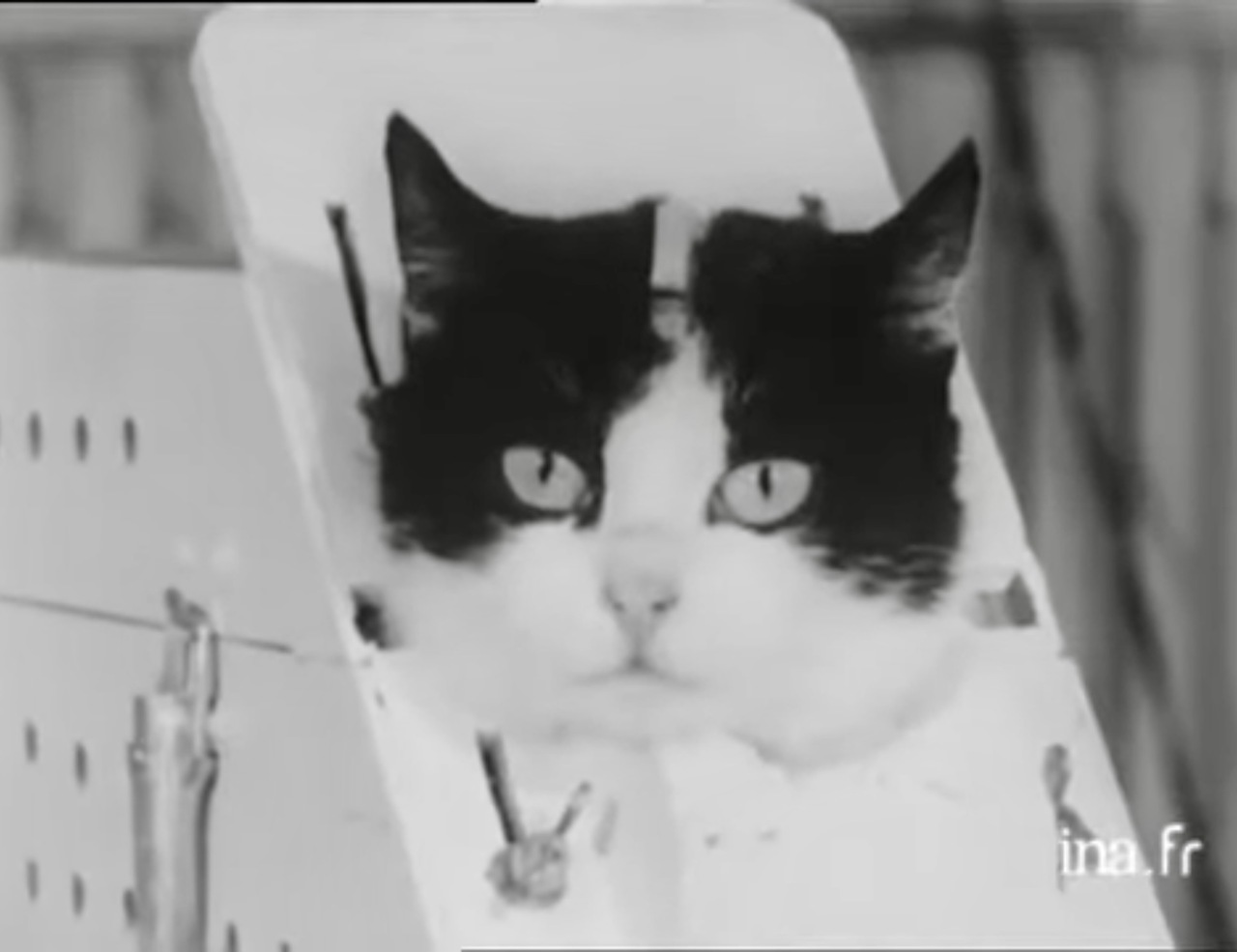

After several days of preparations, a small black and white cat identified as C341 was chosen to become the world’s first cat in space. Around 8 a.m. on October 18, 1963, cat C341 took off on the tip of a Véronique rocket.

Surgically implanted electrodes in her skull measured her brain activity. Probes measured her heart rate, a device attached to her leg sent a small electric current to her muscles to test her responses, and a microphone recorded the sounds she made.

Rising 157 kilometers above Earth, the nose cone separated as planned from the rest of the rocket. Then it fell, faster and faster, tilting and rolling as it re-entered Earth’s atmosphere. This was the phase the cat disliked the most, judging by her accelerated heartbeat.

The parachute opened and pushed the capsule into a slow descent. Ten and a half minutes later, the cat was back on the ground, just a few kilometers from where she had left. A helicopter flew to retrieve the capsule and its passenger, who was shaken but alive.

The next two months were spent conducting tests on the cat. Had her exposure to outer space affected her behavior, her muscles, her nervous system? Finally, the investigators turned their attention to her brain, and at the time, there was only one way to examine it.

“They put her down so that they could look at the areas of the brain, especially around where the electrodes were to see if they had caused any issues,” explained Kerrie Dougherty, a space historian who teaches at the International Space University, on the RFI website.

“As it turned out, apparently there weren’t any. So she probably could have gone on living happily for some time longer. But again, it’s one of these things: at the time they didn’t know that until they did it,” she added.

In 2019, Félicette was honored with a memorial statue in the International Space University’s Pioneers Hall. “Félicette’s story is a tiny little part of that quest to understand what it is that space does to the living organism,” noted Dougherty.